Chester Bennington's Volt Festival Gig

By Rory Winston

Could you see it coming? Could you even hear it coming? No. It’s not very likely anyone had. At least, I didn’t. Not when it came to Chester Bennington. And despite the long succession of suicides running from Chris Cornell to Robin Williams, all the way back to when my own dear friend took her life years ago, I – despite all my own proclivities towards depression – didn’t see a single one of those coming. Just like Bennington didn't see it coming for his dear friend of years, Cornell. The truth is, it’s not likely they themselves had known what moods would be fatal until they presented themselves. At least, not until the very last week, the very last night, the very last moment, when they decided – either with certainty or simply with partial commitment that, sadly, happen to work out to carry out that which so often tempted them before but proved no more than a passing mood. And still people ask. Did I notice anything odd at Volt Festival while Linkin Park was playing? Was there a moment, a single instance when…? A harbinger of sorts, a telltale sign….? No.

Having grown up with Rage Against the Machine, Nirvana, Alice in Chains, Tribe Called Quest and a bevy of groups that influenced the alternative nu metal rap rock that became Linkin Park’s genre, it was hard not to share Bennington’s mood swings, well rhythmed angst and sharply juxtaposed directions that veered from cynical to sensitive to haunting in the matter of moments. Then again, it’s not likely that even Bennington had planned out the actions he’d be taking just weeks later. At least, not on that sunny June 27th when, in the company of other band members, he looked out over an enthusiastic fairground in Sopron, Hungary as Linkin Park played in the country for the very first – and what was clearly Bennington’s last – time. Certainly, not on that balmy day when Bennington performed songs ranging from the more forgettable electro-poppy Talking to Myself (the third track on their new pop-infused album One More Light) to the evocative classic In the End - a show-stopper that was followed by encore numbers such as Numb.

To be sure, Volt Festival is a strange concatenation of longing and memory - one that lives up to the multiple (if inadvertent) connotations inherent in its moniker. Though named after a popular local cultural magazine, Volt culls forth very distinct images that range from voltage – the electric potential energy inherent in something – to the Hungarian word ‘volt’ meaning ‘had been’ as in ‘all that which had come before.’ While it may be an unintentional bilingual homonym, there is something to the notion of ‘things passed’ holding the key to our as-of-yet ‘unrealized future.’

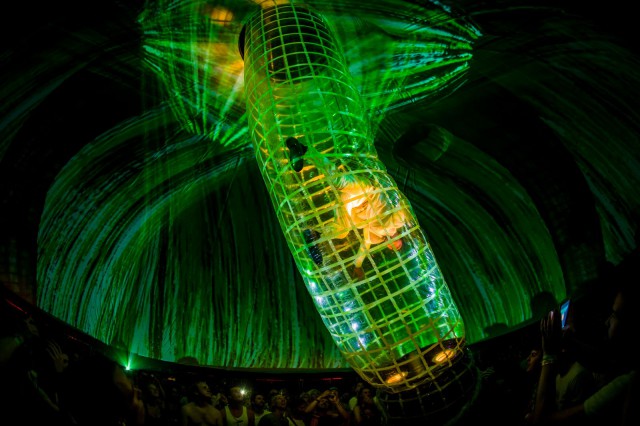

As with the best music, emotive moments are built on acquired taste while nuance depends on finding exciting variations to oft-recurring themes. The echo of past motifs sits dormant in every potential song. When it comes to great rock festivals: they carry the ‘electric feel’ of the past, releasing otherwise dormant ancient energies. A primeval mood hides in the contemporary. An unspoken pagan world is alluded to in each rocker’s chant. Behind the rhythm, layers of ritual. Behind the dancing masses, hundreds of thousands of years of tribal communion - body paintings, colorful powders, flashy tattoos. All the paraphernalia, noise and sets are merely echoes of a long lost world - a primordial garden that beckons us, albeit in a distorted way, asking us like Nirvana to come ‘as we are, as we were, and as we are, likely, meant to be.’ To come and to become in the very same instance. Like the best of rock festivals, Volt is the very essence of this dichotomy – it is a rich field where nostalgia and nuance dance with one another, where each spectator unwittingly acts out a past destined to alter another onlooker’s future.

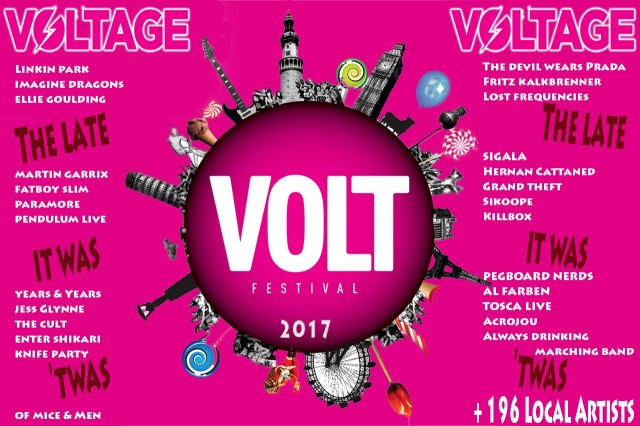

In musical terms this juxtaposition means that the young contemporary DJ Martin Garrix works the same audience as Fatboy Slim while Australia’s Pendulum plays alongside the 80’s British rock band the Cult. Here post-hardcore experimental rock band Enter Shikari takes over from R&B singer songwriter Jess Glynne, iconic indie pop Ellie Goulding precedes US heavy metal band Of Mice and Men, Australian electro dance duo Knife Party warms up for the US alt rock pop punk band Paramore, and blues and soul inflected indie rock band Imagine Dragons leaves us in the hands of those like the house dance pop Dj Sigala.

Besides the battery of international superstars, the festival is rife with Hungarian oddities as well - those that range from well-established songwriting legends such as Janos Bródy to alt rhythm and blues rockers Kiscsillag, melody-laden Quimby, the highly theatrical Anna and the Barbies and their more self-ironic post-modern counterpart, Peterfy Bori and the Love Band. As for some of my own personal favorites, they came in the form of a newer generation of Hungarian artists such as the infectiously humorous Elefánt, the highly emotive Marge, the Hungarian Franz Ferdinand-styled band, Ivan and the Parazol, its spinoff indie folk band Fran Palermo, the electro-chill feminine answer to Chris Isaak in Belau, and the haunting artistry of Babé Sila.

Though the focus remains music, an old school ambience pervades Volt - a traveling carnival-like atmosphere evinced by period-evoking amusement park rides, barnlike dance joints and copious amounts of reasonably priced local wines, craft beers, cocktails and foods. More importantly, the audience itself is strikingly diverse with visitors of all ages from all walks of life. Located in close proximity to the Austrian border - Vienna being the closest big city - the Festival sports has grown in both size and international repute. Despite the recent attention, Volt has nevertheless maintained a Mid-1900’s kind of appeal with its limited number of stages, its easily walkable grounds, and its highly manageable venues.

The overall feeling is that of meeting world renowned artists within the context of their own hometowns. Though a good number of the visiting bands and artists come to Volt at the height of their careers, the quaint setting endows them with a sense of vulnerability, making their presence feel almost intimate in nature - as if they were neither more nor less remote than local bands. It is this laidback atmosphere that lasts the entire duration of the festival.

Removing the veneer of fame and the artificially generated distance it often engenders, Volt turns otherwise inactive voyeurs into genuine participants. Despite the exceptional effects, elaborate lighting and projected images that went into many shows, it was a given that the bands performing sensed the individual presence of audience members throughout.

Still, like many, the thought of Bennington continued to return as I continued to rack my brains, for clues. But, although hindsight often comes to the rescue of memory, making irrelevant moments significant while turning pivotal moments into negligible ones, there’s little I recall from Linkin Park’s Volt performance that makes his demise more comprehensible. No eureka, no flashes of insight, no telltale omen temporarily forgotten. Not a single image that resurfaces in my dreams to presage his death or foreshadow the onset of a severe depression. But why would an audience member be expected to detect something when even those closest to him sensed nothing just days prior to his suicide.

No I hadn’t seen, heard or sensed it coming. Not by a long a shot. What I did sense on those glorious days in June was voltage… pure voltage - potential energy being released, an ancient ritual being realized, the electricity of emotion as it surges from performer onto onlooker, working its way through the audience, holding all who come in contact with it in its grip. It is not what Bennington died from but rather what he, and those like him, live for. As the renown Linkin Park song goes, Bennington, like many must have felt Volt was “somewhere I belong,” somewhere that ‘Lost in the Echo’ of our collective past, somewhere everyone can remove social constraints, connect and “Burn it down” together.

Though many Hungarians who attended the festival, and many Brits who attended Linkin Park’s later and final gig in Birmingham continue to speculate about whether Bennington acted any differently than usual, the fact is that a person can remain alive when acting out of character as easily as he can off him or herself when otherwise being very much in character. Neither usual or unusual behavior is a failsafe way of measuring volition and level of commitment. The truth is people are as likely to succeed when only half-sure as they are when they are certain of what they want since positive results are as common to happen when one least expects them as negative results when one would expect them. This by no means implies that we need not be vigilant and do whatever is in our power to stop a suicide attempt. If we even half-suspect it, we are morally obligated to do whatever we can to prevent it because ignoring it is tantamount to abetting the suicide. That said, it does not mean the signs are always present or readable.

On that day of late June, I, and, more importantly, many who had seen Bennington up close, and known him for years, would say they weren’t. On that day, just weeks before his death, Bennington seemed to be enjoying himself - singing, dancing, in perpetual motion and filled with as much hope and angst as he likely had been on the very first day he took to the stage

Press here to find out more about volt