THE INDELIBLE DEL & HIS IMPROV EMPIRE

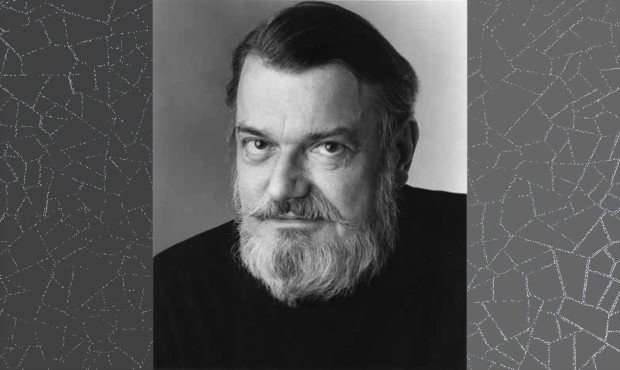

Although you may have heard the legendary skull allegory, few people today working outside the field of comedy are familiar with the name Del P. Close. Yes, he’s the guy who on his deathbed bequeathed his skull to be used as a credited prop in the Goodman Theater’s then upcoming rendition of Hamlet. Although lifelong collaborator and cofounder of the Imrov Olympics, Charna Halpern, later confessed that the coroners refused to allow for the discrete decapitation, for the improve artists who had spent a lifetime working with mockups and imagined sets, the purchased anonymous skull from a local medical supply would forever be revered and treated as Close’s own.

Besides the fact that Del Close had coached Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, John Candy, Chris Farley, Jon Favreau, Tina Fey, Bill Murray – well, you get the drift, he was also considered one of the most prominent influences on the development of Improv theater as we know it today. Having taken it from the late sixties where it departed from being merely a technique to enhance acting skills and turned it into a legitimate art form in its own right, it is his name being sported over what had recently been the 16th annual Del Close Marathon – a 56 hour long celebration that included everything from the renowned Upright Citizens Brigade to incoming acts from all over the world.

As someone who has worked with comedy primarily in the capacity of a writer, I had over the course of many years made the mistake of relegating Improv to the limited role of emergency aid for dead end scenes. Improv for certain playwrights is the theater world's ICU. A sketch or scene looked like it was convulsing, the flow of dialogue wasn’t getting to audience’s brains in time and, the very next day, a gifted director would wheel the entire scene in on a gurney and allow the troupe of actors to attempt a resuscitation. Having already tried traditional theatrical cures such as script doctoring and a series of invasive ‘kill your darlings’ surgical maneuvers, it was at this point that the pagan rites of Improv would commence. Relying on the momentum, associative skills, and the dynamics of unrehearsed interactions by gifted actors, scenes were revived like some golem – occasionally inhabited by the voice that had been present earlier on but just as often taken over by some unidentifiable being becoming its very own animal.

Intrinsically, Improv is, of course, way more than merely a technique used to either revive a scene or aid an actor in fleshing out a role. It is a craft in its own right – a craft, that I began to appreciate more and more throughout the years of working with very gifted stand-up comedians and, more specifically, Imrprov artists. The field was evolving and drawing in a wider audience – it was opening its doors to entirely new groups of young people.

In an interview I conducted several months back with Hot 97’s Cipha Sounds, he explained the strides taken to bring Improv to urban kids in otherwise rough neighborhoods. What used to be mostly an art form practiced in the domain of a university crowd was turning into a valid means of expression for a group of kids who would otherwise have relied solely on rap or stand-up comedy. It was an art form that lent itself to a different sensibility than the one required by either of the other two. You could express touchy and highly personal issues with a distance unknown in stand-up while being utterly devoid of the usual posturing that often inhabited rap. This was not proclamation or self-expression; it was interaction. This was not a mapped out concept but a theme in the throes of change. Likewise, the fact that nuances popped up during a performance meant that the audience was able to share in a performer’s first time revelation. Instead of a pre-rehearsed crescendo where the performer knew his position on a certain subject in advance, Improv could lead to an epiphany had on stage. It was less cynical somehow, less about just the quality of the delivery and more about the new places it was headed. It could even – given that everything came together just right – bring simultaneous and unpredictable solutions to the dilemmas of both audience and performer alike.

Despite all the marvelous experiences I had watching Improv, it wasn’t until I had gone to write a pilot for a TV series in Finland that I understood the level of contribution one very gifted Improv actor was capable of making while on the set of a television show.

While waiting for my Finnish fiancé to return with me to New York, I tried to make good use of my time in Helsinki by coming up with what I felt was a unique concept for a comedy-driven TV series – one in which the audience would be kidnapped and taken hostage into a parallel universe that could breech all the more universal and touchy subjects by playing off EU-related themes and local eccentricities. Like many such TV formats, it underwent a series of different collaborators, producers, revisions and working titles over the years. From a highbrow concept to a more straightforward SNL-type of production, it bounced around the networks garnering interest and was close to being green-lighted on several occasions only to be set aside due to budget considerations and questions relating to the track record of the respective producers involved. Just when I had all but given up on the show, a new set of circumstances had rekindled the flame.

Having befriended a highly gifted DJ and radio host from the UK, Joelle Reefer, I explained him the content of my show, read him some excerpts and, no sooner were we done with our first meeting than he suggested I do my own talk radio show while finalizing the TV script. The move was serendipitous since not only was the radio station a good way to test new material but the English speaking station was the perfect venue for my mythical comic ‘ant-terrorist terrorists’ who would kidnap the audience. As both Joelle and I concluded from our many conversations, the radio station where we worked was a caricature of an American Hip Hop station – one that in its effort to promote minority culture was unwittingly stereotyping the black community.

Although the owner of the station may have had a genuine affinity for hip hop and R&B music, he desired nothing more than to have his otherwise sophisticated UK born announcer sounding like he had come ‘fresh from the ghetto'; while I was expected to go from observational humor to what can only be described as the audio equivalent of slapstick. Since being more 'gangsta’, using more 'yo’s', and speaking a very affected form of Ebonics seemed to be synonymous with inhouse credibility, it became increasingly hard to believe that we were actually in Scandinavia and the year was 2013. As for the news that white people would do well to steer clear of using the ‘N’ word, it never seemed to have penetrated the upper echelons of the administration. It’s use was not only systematically overlooked but positively applauded as constituting ‘cool’. In short, we were not only from 'the streets' that did not exist on any local map, but we were from streets that existed nowhere since the late 90's as we drove our Hummer to a festival at a time when the rest of the world aspired to smart cars.

To be fair, these abuses were not ones practiced by the DJ's who ran their weekly shows oblivious to the underlying policies - they mostly managed to play their own tracks and maintain a respectable distance from the embarrassing platform. As for the staple programming and playlist, that was another matter entirely. With all the posturing and righteous indignation of an opportunist cleric, the station embraced an ever changing list of topics that it pretended to be extremely concerned about - this list of course was subject to basically two things: (1) the things our possible sponsors and investors would find pleasing to hear (2) things which happened to be 'globally cool' and acceptable to be worried about on a given week. If news broke that Somalian immigrants were being attacked by right wing fanatics in Finland that would hardly compare in importance to the fact that Kanye West felt that corporations were stereotyping their consumers.Since all this was done with uncanny earnest, the venue lent itself to a level of self-irony that would otherwise have been unavailable in the highly educated country of Finland.

In short, for a few of the regulars (Joelle, my co-host Karo and myself), the station was heaven. It was a grotesque – if naive – example of all those politicians and businesses that had exploited the causes of others without ever even going to the trouble of understanding what those causes were about. By simply doing riffs on our own hypocrisies, we were able to tackle every global issue from homophobia to Islamophobia to racism to the mock-concern often displayed by Western politicians for the plight of the third world.

And what was even better was that - unlike our audience - those running the station didn't seem to notice. It is a testament to the sophistication of the audience that the more ambitious our material became, the more our fan base expanded and grew.

If there was anything we had learned over the many months was that the average member of the Finnish audience was far more savvy than those who made their living being on the "forefront of local media". Youths were globally aware and had grown up on the best in international broadcasting, while those who decided on what to broadcast for them were often too busy competing with one another to notice what was going on abroad.

After several months of testing material and planning, we had done it. We had attained a level of popularity that helped convince the owner of the station to become the executive producer for the TV show I had written. A month or so later and we were shooting the pilot. The one hitch: it would be in a language I didn’t understand – namely, Finnish. Though I had the benefit of a remarkably good translator – my fiancé and part-time radio co-host, Karolina Alanko – who was not only adept at pulling off wordplays but also of transposing concepts and finding cultural equivalents, it was often difficult for the respective directors to explain to the actors what types of personas or stereotypes they were supposed to be playing off.

It was at this stage that I had the fortune of meeting Miska Kaijanus, a highly gifted stand-up comic and Improvisation artist with a background in acting. Not only did Miska approach each role with layers of nuances, but he turned a room of virtual strangers into a veritable acting troupe. Schooled on a large variety of shows from all over the world, Miska was the new generation of performing artist - one that complemented all his formal training with incessant viewing of the best artists globally. Downloading, watching you-tube, grabbing names and techniques off the internet, he had groomed himself into the type of performer who competed with the very best on a daily basis. He was familiar with what was going on and relentless in his pursuit of excellence. Waitering his way through California, he fearlessly hit the comedy clubs of LA as a total unknown just to get a better sense of what he was up against and where he was headed. Not content on working in one genre or even in one language, he threw himself whole-heartedly into performing in both English and Finnish, careening from stand-up to improv to music-based parody. The result was a distinctive voice with a unique ability to create an insular micro-universe around himself that was, nevertheless, accessible to all those who desired to enter. It is both his highly punctuated and precisely timed moments as well as his utter sensitivity to spontaneously react to what is around him that allows him to maximize on a given situation.

If there are successfully directed moments in many of the sketches, they owe as much to Miska's vision as they do to the respective directors involved with the show. It was Miska’s interdisciplinary approach – with its grasp of acting, directing and even writing – that gave him both an understanding of what each role entailed, as well as the language with which to communicate these aspects to the other actors. And, it is precisely this kind of range that makes Improvisational Artists a very necessary component of many shows.

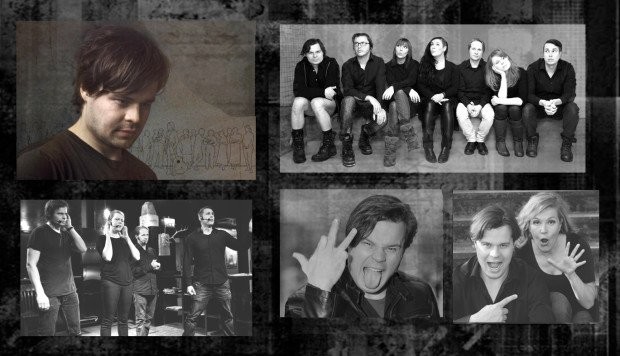

It is a pleasure to note that along with hundreds of other improvisational actors that were performing at one of the eight venues for this year’s DCM 16, Miska Kajanus took to the stage in the company of the VSOP improv group,(known in NY simply as Team Finland). With a cast that included New York trained Ulla Virtanen (American Academy of Dramatic Arts and UCB), Tuuka Tiihonen, Jussu Puhakka, Sanna Saarela and Katja Lappi, the performance entitled That Day in Finland proved both fascinating and highly entertaining to all those who haven’t managed to see Finland’s upcoming generation of improv talents.

With artists traveling from all over the world to perform what often amounts to no more than 15 minutes of stage time, the Del Close Marathon is non-stop weekend of 24 hours a day performances – one whose diversity and flair ensures that that there are many dedicated audience members capable of watching runs from morning to night to morning again. With brilliant writers like Chris Gethard, Key and Peele, Nick Kroll, Thomas Middleditch, Ben Schwartz, Diamond Lion, Jason Mantzoukas, BriTANick, Broad City cast members,and plenty of musical improv, the enactments are bound to possess both élan and staying power. In addition to longfrom improv by UCB that may include special guests from SNL, 30 Rock and the Colbert Report, ASSSSCAT 3000 – with legendary Amy Poehler, Matt Walsh, Ian Roberts and Matt Besser – will once again be closing the festival.

In tune with the 1960’s communal zeitgeist, Del Close was convinced that art could be done ‘by committee’ – by a group that worked like an organism in much the same way a single human brain functions but exponentially better. Under his tutelage, actors would take a suggestion from the audience and play out improvisations. These small set-ups would eventually give birth to elaborate structures where parts would naturally echo one another, motifs would recur and themes would rhyme. For Del, every word spoken, every action undertaken was part of an emotional game meant to manipulate someone; his art form – which he likened to a sport in terms of the audience routing for success – allowed those attending to see otherwise innocent moments in their own lives as the heavily veiled bearers of deeper subliminal concerns. If Dem 16 is anything to go by, it is clear that the need for communally witnessing the unplanned interaction between human beings has not dissipated over the years. Judging by the turnout, The internet age has people craving art that is live and spontaneous more than ever. Though Close’s last wish to have his skull used in place of Yorick’s was not honored, the thoughts that drifted within throughout his lifetime have an entire festival bearing his name as their living edifice: ‘Alas, poor Del, it seems your contributions are still known – a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy.’