By Rory Winston

**********

Syndicated with the permission of The Resident Magazine, New York where my article first appeared. (All Photos of Sampsa and his work courtesy of: Anni Maarit)

**********

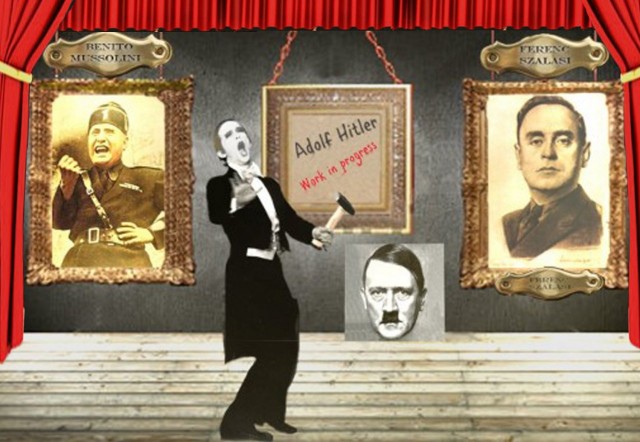

It was in 1944 at the height of the holocaust when a locally renowned actor staged a performance in Budapest’s largest theater – one regularly frequented by Nazi officials and soldiers alike. The event took place just a few weeks after the Nazi-backed Arrow Cross Leader, Ferenc Szalasi, had taken control of Hungary, at a time when even the slightest anti-fascist provocation could result in an immediate death sentence.

The actor walked out onto a barren stage, bearing three paintings: one was a portrait of Szalasi, the other of Mussolini and the third of Hitler. Staring blankly at the somber audience, the performer proceeded to mount each portrait on a wire without uttering a word. Shortly after hanging two of the portraits, he picked up the last one, held it aloft and – as if apologizing to the figure in the painting - announced:"Patience, patience, my dear Fuhrer… like the rest, you’ll be hanging in no time".

As dread gave way to gasps and uncomfortable titters, a sudden uncontrollable wave of laughter seized the audience. It floated over the room like a roar - terror and relief colliding in a single instantaneous guffaw. The gravity of what had just occurred was understood by all. Each person present had, inadvertently, become a participant in mocking the very regime he or she was intent to uphold. A message had been delivered; and the recipients of the message had become part of the content.

TAKE IT TO THE STREETS

"I may go to the movies to escape; but when it comes to novels, I better be hijacked in the opening scene and be on my way to a new destination that will leave a permanent mark on my soul... cause otherwise I am going back to the gate and getting on another flight"That's my brother's view on art as opposed to pure entertainment. And I'm beginning to think there's something to it.

The idea of making a political or social statement through art is not a new one. As far back as 1810 Francisco Goya did an understated protest against the Dos Mayo Uprising and the Peninsular War in his Disasters of War series. But what was different in the Hungarian performance was the idea of reinventing the bystander as an integral part of the work itself. Although inciting change through Resistance Art and Activist Art had become a recurring theme from WWII through the 60’s, it was not until the late 70’s – when graffiti artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat appeared – that the lines between bystander and audience would blur for a second time.

By involving pedestrians in a public space, street artists (those who employed the medium of graffiti in delivering conceptual works of art) were not simply engaging or interacting with a consenting audience; but they were seizing upon an unwary public, provoking unsuspecting cosmopolitans to think. In short, a non-audience was forced into becoming unwitting elements in an artistic process. While billboard advertisements were busy feeding subliminal information meant to manipulate and/or lull the masses, these works assaulted perception and incited people into reevaluating all that which surrounded them. Nowhere was this manifestation of altering public space into a catalyzing agent clearer than in the Bristol Underground Scene where Inkie, 3D, Nick Walker, and that ‘world renowned anonymity’ Banksy had taken to the streets. Steve Lazarides was one of the first to recognize these emerging voices; and it would take him less than 15 years to turn works officially referred to as vandalism into high listing auction house commodities.

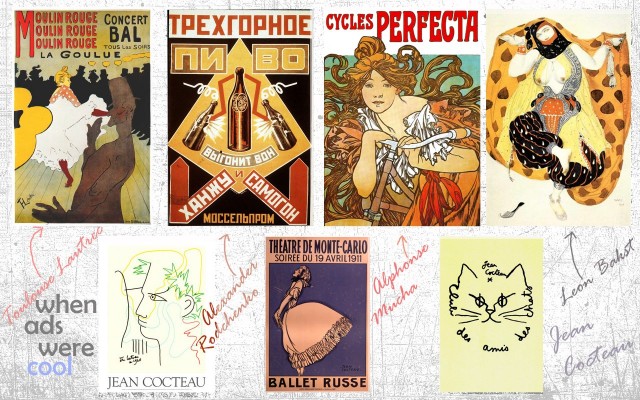

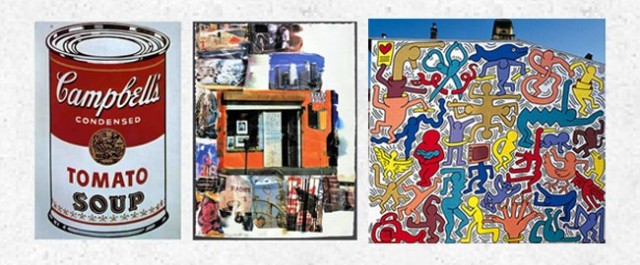

While earlier artists like Alphonse Mucha, Toulouse Lautrec, Jean Cocteau, and Alexander Rodchenko had taken fine art aesthetics (whether neo-primitivism, constructivism or art nouveau) and employed them in the service of posters, advertising, and political campaigning, the 80’s graffiti oriented artists did precisely the reverse. They used advertising and campaigning aesthetics to create artistic statements. Having grown up on the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol – artists that explored the relationship between art, news and advertising (whether in the form of consumer products or celebrity culture) – it did not take long for a new generation to see that the natural next step would involve breaking the boundaries between museums and the real world – a domain that till now belonged solely to billboards and, what was officially referred to as, vandalism. Soon, ‘public thought experiments’ began to take shape. As Keith Haring stated, “My shop is an extension of what I was doing in the subway stations, breaking down the barriers between high and low art.” But even more than than these barriers, it was a time when two dimensional paintings started to flirt with 3 dimensional spaces and the wall between the artistic realm represented in the work and the ‘real location onto which it was drawn’ would become indistinguishable.

And this was just what happened when Banksy hit the scene. Using stencils, drawings, graffiti, color layering, Banksy began to create a series of works that were intended to satirize authority and mock those considered in power. Instead of simply using walls and public spaces as a canvas, his pieces were in direct dialogue with their settings. They were juxtapositions specifically designed to redefine what was originally present, creating a meaning unintended by the original design of those spaces. If there was a crack in a wall, it was a perfect place for a drawn rat to be running out of. If there was a real window, why not have a drawn image hanging from it. More to the point, if the location existed to sell consumer products or heighten patriotism, why not reinterpret the respective domains so that they became anti-consumerist and ant-nationalist in nature. With an anti-capitalist, anti-fascist and existentialist bent, Bansky turned average street corners into meaningful reflections on our society’s hypocrisy, greed and absurdity while highlighting the alienation, despair and boredom that such a system engenders.

WHEN OFF-THE-WALL IS ON THE WALL

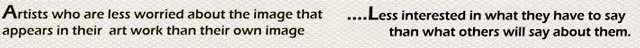

By the time Frank Shepard Fairey hit the scene, the public had become savvier. Most were aware that Street Art was more than just urban expression and had the potential to lead to financial success and fame. Likewise, art critics had caught up and had learned to judge street art on more solid artistic criteria. It was at this point that a very peculiar phenomenon took place. Street Artists themselves became image conscious. They were no longer trying solely to provoke people to think but were incorporating the eventual criticism of their works into the works themselves. To clarify: artists were less focused on the actual art than they were on the possible interpretations that their work might or might not evoke.In an effort to secure a more profound review – Street artists, aware of the attention they were receiving, injected their works with philosophical attributes of which the works themselves were often devoid.

As an example, Fairey did an André the Giant Has a Posse sticker campaign in 1989. It didn’t necessarily have a deeper meaning than your well-executed mock-up of a poster with a parody effect. But in an effort to maximally exploit the potential of this catchy drawing, Fairey created an Obey Giant campaign – one that drew heavily on oblique and rather strained parallels between his image and Martin Heidegger’s concept of Phenomenology. It did not take long before Fairey was borrowing slogans like ‘the medium is the message’ in an effort to gain intellectual credibility for what was no more than a glamorized sticker campaign (a sad regression in terms of slogan choices considering Marshall McLuhan had already coined “the medium is the massage” by 1967). Though Fairey came off sounding no better than a first year French postmodern Philosophy student desperately misquoting Jacques Derrida, he did earn a hefty income from T-shirts and legitimate advertising work.

PRIVATELY OWNED PUBLIC

In the end, Fairey had become as exploitative as any other marketing agency, but, the trick was, he managed to retain his status as an anti-capitalist and anti-establishment persona while doing so. Many like Fairey had become what I would call Sunday Anarchists – those who lived a merrily middle class life, benefited from all the marketing they publicly reviled and then went out on the weekends to rail against the inequities befalling mankind as a result of those ruthless ‘other’ capitalists. This is not to say that Fairey’s themes were all contrived, but we do have to acknowledge that the devices he supposedly created solely for the purpose of delivering heavily anti-consumerist messages have been rented out by him in the form of Guerilla marketing to Pepsi, Hasbro and Netscape. And he was not alone.

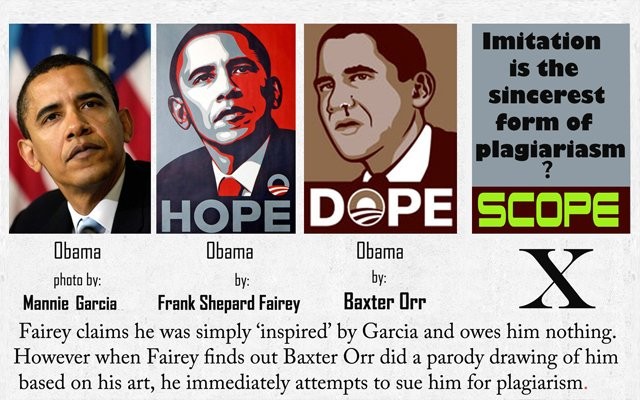

Inevitably the issue of ‘art in service of a self-promoting agenda’ as opposed to ‘art in service of art or an ideal’ did collide in the form of Copyright issues. Fairey had been indicted by his own espoused ideals. The man who scoffed at allegations that he had misused other peoples images without proper citation was suddenly suing someone else for creating a work of art that was based on elements of his own work. The very same artist who had failed to mention the photographer Mannie Garcia on an image that earned him a congratulatory letter from President Obama for helping his campaign was suing Baxter Orr for his use of the Obey Giant, calling Orr a parasite.

On the one hand, it was perfectly okay Fairey to cite ‘Fair Use’ when making ads for Saks 5th Avenue based on – of all artists – the devoted anti-capitalist genius Alexander Rodchenko; on the other hand if someone used anything of Fairey’s it would be greeted with animosity and litigation. To use the terms prevalent in the music industry, when Fairey stole something it was a ‘homage’, a tribute, at worst, a remix; but if someone else dared to be ‘inspired’ by Fairey, it constituted ‘plagiarism’ in the first degree. The formula became relatively easy to understand: if you were famous then stealing ideas and images was a gracious tip of the hat to quietly acknowledge the past, if you were unknown, it was a vile act by a frustrated individual who warrants merciless ridicule and a law suit.

STREET SMART ART

It seems only fitting that the issue of Copyrights has brought one of today’s most interesting Street Artists into the limelight – an artist who, paradoxically, eschews any form of light whatsoever in that he, like Banksy, has kept his identity utterly anonymous. In addition, the artist in question is one who was neither a defendant nor a plaintiff in a litigation involving a copyright scandal, but one who chose ‘Copyrights’ as the subject matter for creative reflection with an eye to changing the policies that most governments presently advocate. The artist I am referring to is Sampsa. Having been fortunate enough to have met Sampsa many years ago – at what I can only refer to now as an undisclosed gathering – I have made it a point (by way of readily available, if slightly convoluted, means) to stay in regular touch with the man ever since.

Sampsa’s interest in copyrights is the result of a very specific set of circumstance: The Finnish government had proposed an increase in the severity of punitive damages for copyright infringement at a time when similar laws proved to be of little value to the very artists on whose behalf they were being initiated. Sampsa thought the entire notion was ludicrous and benefited only the few. If anything, it made it more difficult for artists to be in direct contact with consumers and impeded the sharing of important research material.

As Sampsa recently explained over the phone:

What made matters worse in this case was the Finnish government’s complicit nature. Throughout our recent history, our government has regularly tried to please foreign governments. But in this case, it’s not simply war debts being paid off ‘beyond and above the call of duty’; but our government going to the point where it’s willing to strip its own citizens of basic human rights solely in order to please some entertainment industry lobbyists. Basically, police now have the right to enter and search someone’s home merely for being suspected of peer to peer sharing.What began as one man’s ‘street art’ response to a proposed amendment in Finnish law soon turned into an all out initiative to change those very laws. Sampsa’s art work, in collusion with Open Ministry – the primary motor behind the action – and the Finnish Electronic Frontier Foundation, managed to garner public support. In the end, the action obtained the 50,000 votes required by Parliament to challenge the integrity of the proposed amendment.

Working in cahoots with the well-known Finnish artists Jani Leinonen (of hijacking Ronald MacDonald renowned) and Riiko Sakkinen, Sampsa created Exhibition 49,999, an awareness campaign that culminated in a website blackout day and brought in the necessary number of votes to make Finland the very first country in the world to impel its parliament to reconsider copyright laws. This is historically speaking the first crowd-sourced copyright initiative ever.

Sampsa went on to add:

Sadly, the Initiative has yet to advance to Parliament for a vote. I believe the Chairwoman of the subcommittee overseeing our proposal could be to blame. Raija Vahasalo – the person holding that title – has thus far refused allowing impartial experts and academics to be heard. In fact, virtually all documents prepared for the Parliament and its subcommittees have been created by the very industry lobbyists against whom the proposal is designed to defend. This is perhaps the single most relevant argument for concluding that Finnish democracy has not undergone a form of hijacking unknown since the days of Kekkonen (the Post-WWII virtually undisputed President-for-life). 52,000 people demanded a proper discussion on copyright but a single person has managed to bottleneck legislation by her continual refusal of honest and transparent debate. It defies logic how anyone can justify not listening to impartial experts. In a country like Finland where we regularly poked fun of Berlsuconi’s abuses and Italian juridical protocol, it’s strange to see them go off the deep end like this. Still, the possibility of change is out there… and it’s precisely people like Raija who are capable – when seeing the whole picture – of making a difference.SAMPSA'S SORTIES

That same year, Sampsa’s other pieces entitled Spineless SAFA and Vaino caused a stir as they attacked zoning ordinances and the lack of local investment for local artists, exposing the fact that many who make money from hyping nationalism actually invest most of their finances abroad.

By 2013, Sampsa was in Paris targeting the HADOPI law which – like the aforementioned Finnish laws – promotes the distribution and protection of creative works on the internet. Describing the law as hypocritical and a misallocation of funds, Sampsa created an anti-HADOPI stencil-based work that he left on the walls of the Butte aux Cailles neighborhood. While the actual message (the text exhorting the people not to give in to the HADOPI’s thought control agenda) had conveniently been purged, the government did leave the graphics intact. Clearly the image of a child being chased by a large mosquito was to the state’s liking; while its meaning (‘the blood sucking HADOPI’) was not. The entire raison d’être for the piece having been expunged, the innocuous aesthetics could remain jusqu’à la fin du temps. The irony of the city having censored an artist who had spoken out against a law intended to protect artists is not lost on Sampsa.

In a later Paris series entitled Obsolescence is King, Sampsa took on the idealization of the internet age (that many romanticize as being synonymous with democracy) by depicting the paragon of IT development, Steve Jobs, as no more than a clown king of redundancy – a figurehead attended to by third world child laborers who mine minerals for gadgets that first world children end up worshipping. Unicef featured an article about the campaign on an online magazine about child labor.

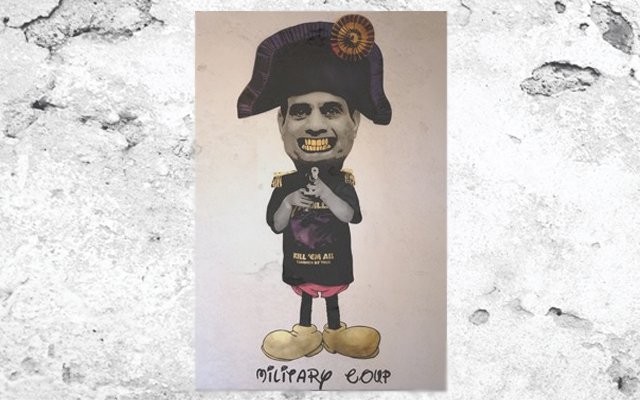

For his overt support of Pussy Riot, Sampsa was soon invited to participate in a street art event for activists in St. Petersburg. Shortly, however, his piece Little Brother is Watching You was censored from appearing in the Museum of Modern Art and Design in Omsk, Siberia where it was slated for exhibition. The United Russia Party seemed to have reservations about Vladimir Putin being portrayed as a dwarf. Similarly, there was no relief in sight as Sampsa came out in support of Konstantin Altumin’s work done on behalf of the LGTB community by portraying Putin as an alluring transgender girl in a swim suit. In the extremely homophobic society that is Russia, having bathing beauty Putin demurely posing for some unseen admirer is not exactly something that fits into the shark-riding, lion-taming, bear-wrestling image Putin has been trying to project.

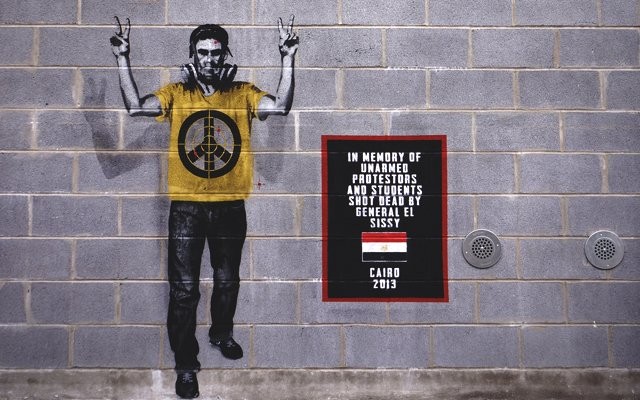

More recently Sampsa has been involved with the plight of those in Egypt, and has even gone as far as teaming up with Egyptian Street artist Ganzeer on a joint project. Along with magazines such as Vice, Occupy Times, Huffington Post, and the Guardian, Sampsa is raising a campaign to engage the UN Security Council. In an extensive interview that sampsa recently gave to RT’s Washington DC based host Abby Martin of Breaking the Set, Sampsa – wearing his usual black mask and hood – spoke out about the present Egyptian regime and went as far as to claim that General El-Sisi was a war criminal responsible for an untold number of deaths. Whether one agrees with this perspective on the present situation or not, one thing is certain, the comments elicited enough tension within the Russian media that the interview is now nowhere to be found on either RT or the Breaking the Set archives. Though Sampsa is unwilling to comment on the reason for such an unceremonious withdrawal of information, it is easy to speculate about the pressure that Russia could have exerted if they felt that Sisi’s position could be jeopardized by the program. After all, two billion dollars worth in weapons deals are no trifling matter. A recent development to this entire campaign – and one that had received media attention from Huffington Post to the Guardian – was the fact that Sisi recently branded both Ganzeer as well as Sampsa ‘terrorists’ (a proper noun that in today’s context is synonymous with ‘target’). Does giving any would-be assassin a carte blanche to target him worry Sampsa? While he makes light of the threat it poses on him personally as a resident of Paris, he is very aware of what such an accusation can do for Ganzeer, an Egyptian citizen presently in hiding.

Reflecting on Ganzeer’s predicament Sampsa explains,

Like any true artist, Ganzeer has always been very critical of anything that stands in the way of people being able to express themselves freely. It’s just disgusting that a man who was pretty hated and threatened by members of the Muslim Brotherhood is now being branded a member of the Muslim Brotherhood by the El-Sisi government simply because he’s critical of the presently murderous crew who – in the name of ridding the country of Muslim Fundamentalists is basically killing all his political adversaries …be they religious or not. No one wants religious zealots installing a theocracy. But the alternative to religion is not Dictatorship. It’s democracy – true democracy like what sent the Egyptians on a course to oust Mubarak and started to take form before extremists from two sides started to muscle in. As for who is in charge now… We’re talking about a brutal despot – not a man fighting to preserve democracy as he likes to pass himself off. And, the truth is everyone in the West knows this… including America’s very own lovely President.

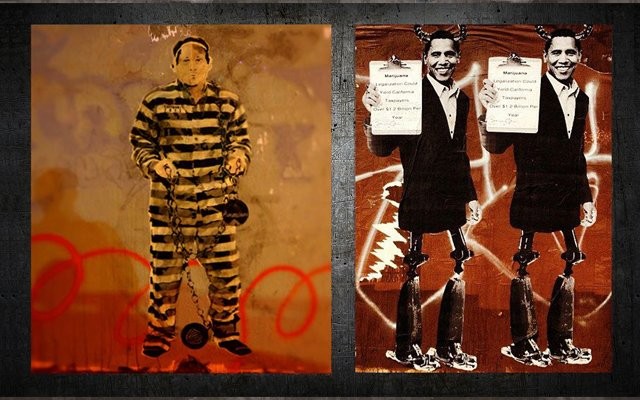

Unlike Fairey, Sampsa doesn’t seem to court political favors or abide by the ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend’ aphorism. When coming to the US, he quickly did a piece in LA with President Obama sprouting horns. Why?

Gereral Sisi wins a Presidential election with tens of thousands jailed and over one thousand murdered. Sisi’s role in this is clearly reported on the BBC and every other major media. President Obama’s response…? He calls Sisi the very next day to congratulate him on his victory. ‘Job well done’ is what, I suppose, he thought. And really, Obama is in keeping with a long tradition in self-serving short term policy makers. There are few dictatorial regimes the US administration hasn’t gone to bed with when it suited their interests. They’re not exactly picky with whom they shake hands. When the cold war was raging, the West was busy helping to militarize the very same Muslim Fundamentalists that our present generation has now inherited. At the time, they were busy congratulating them on a job well done. They are convenient. You don’t have to look to politicians to see this same level of convenient behavior, the same level of disassociation and compartmentalization. Of course, it’s not just ‘them’ (the politicians), it’s us. When people say ‘the System’ is flawed – they speak as if the System was this enigmatic creature that exists outside of us…. No, it’s not the system that’s flawed, it’s ‘we’ who are the System and it’s we who are flawed. Don’t bother asking how Obama orders a drone strike, pets his dog and kisses his daughters to sleep all in one day, without also being willing to ask yourself how can you buy clothing from H&M, purchase an IPhone when you know very well that another human being has suffered or even died to deliver it. Learning how to look yourself in the eyes and not continue ‘hypocritically ever after’ is something we need to do as a species. Reinstating empathy would likely land us in a second Renaissance, a second Age of Reason – one that could easily be called: the Age of Reflection.Interestingly enough Reflection in the world of Street Art is a composite of both ‘reflecting upon something’ and ‘reflex’ – the immediacy of sending a targeted message back to the source in order to effect change and being changed by the very act. This complex dialogue was nowhere more apparent than in the act of Street Artists alluding to the fact that El-Sisi was a terrorist who exploited the word ‘terrorism’.

In order to wage war on any political adversary whether religious or not, El-Sisi had always relied on the word to justify his actions. And here he was being called one by artists. The response by El-Sisi was, of course, predictable: Those insinuating such a thing clearly had to be terrorists themselves. And this is where the real interactivity of Street Art came full circle. It was not what was insinuated about El-Sisi that mattered but his response to it – a response which, in effect, sabotaged all future uses of the word terrorist when employed by El-Sisi. The word had successfully been deconstructed: If Ganzeer – who had actually been hated by Islamic extremists for mocking them before the El-Sissi regime – was considered a terrorist for being critical of El-Sisi, then the word meant nothing.Like the term ‘Communist’ when used by Senator Joseph McCarthy as a weapon used against any and all political adversaries, the word ‘terrorist’ in El-Sisi’s mouth was no more than a device.

Carlo McCormick – the author/curator/critic who penned the book High Times at the height of the US ‘War on Drugs’ was quick to note historical parallels and noted that ‘anybody could be called a terrorist on a whim and without consequence.’ As an unofficial Street Art Historian McCormick compared Sampsa’s #SisiWarCrimes installation art piece with the work of Robert Hambleton in the 1970′s.

WHEN THE WRITING IS THE WALL

Despite Sampsa’s recent American success, it is unlikely that the artist is finished with European collaborations. Having signed a deal with Tuomas Zetterberg – a Finnish-scaled Steve Lazarides whose prestigious Helsinki-based gallery has received international attention – Sampsa seems destined for better financed ‘trouble making’ than ever. With rave mentions for his recent Brooklyn work, and kudos from the same US audience that recently greeted Banksy’s contributions with the words ‘where’s the meat?’ Sampsa may just turn out to be the harbinger of a new direction for Street Art.

From the urban poetry of Basquiat to the powerfully graphic social critiques and juxtapositions of Bansky, we have witnessed a world where public domain works and museum works have become as indistinguishable from one another as have pedestrians from target audiences. By default, advertisements have also become indistinguishable from parodies on advertisements, and calls to duty have become indistinguishable from ironic comments intended to satirize them. As with the advent of postmodernism, many feel that there are few if any new directions left in which art can go. Our celebration of terms like post-irony display a sense that even if a new form of sincerity were to present itself, it would be hard to distinguish it from the cynicism that had given birth to it. And yet, there are still causes we instinctively believe in, things people sincerely want to change. So how is it possible for art – which had once been in the business of provoking thought – to have become so mired in its own self-consciousness that it avoids making direct statements? “Fear of dumbness”, implied the Comedian Robert Klein is a major consideration for artists because they feel their credibility is always on the line. In a sense, fear of sounding dumb often stops smart people from taking action that is smart. It seems that the more naïve and unembellished aesthetics in art have become, the more there is a need for very complex theories and concepts to justify them. It is an age when most creative people feel they won’t be taken seriously if they are attempting to make a straightforward point.

Sampsa, more than anyone out there, knows that street art can be more than a mere catalyst for new perception; it can be an initiator of direct reform. It can have a simple message and still be art. It can be a conceptual piece and still catalyze very specific change. For Sampsa, Street Art is a blueprint for a better society spayed across a city wall – a solid vision that either justifies or rebuffs the existence of the wall itself. In the 1981 indie film, Downtown 81, Jean-Michel Basquiat (later voiced over by Saul Williams) says: “I could see the handwriting on the wall and it was mine”. I wonder if the Sampsa generation will be able to see the same wall and conclude: these words I wrote are not mine; they are the words of public consensus, they are the words that create referendums, they are the words that will become our laws. A wall, it seems, is a most perfect place to create works that will eventually tear down walls.

*******************************************************************************************************************************

END OF PART 1

*******************************************************************************************************************************

RECENT UPDATE TO THE STORY:

Within a week's time Sampsa will be back here with me giving you insights on why he does what he does and just how ambitious his vision of the future is.