WHY FINNISH REVIEWERS HAVE NO OPINIONS

AND THE DAMAGE IT DOES TO THOSE LIKE VESA KIVINEN

By Rory Winston

Photos by Joni Sarkki

PART 1 TRAGI-COMEDY

Behind every great man there’s a woman with a great behind. Admittedly, a silly pun; but If the man in question happens to be appearing in a music video, the statement would not only go from misogyny to unfortunate reality but the body part being referred to in the given equation would likely jump from singular to plural.

Although the rather non-Dynamic Duo, Money and Power, have always held their appeal for both sexes, nowhere is mainstream sexploitation of women more evident than in the ostentatious world of pop music and advertising. We’re already so accustomed to seeing tawdry devices in marketing and so inundated by the nouveau riche sensibility plaguing hip hop that a 14 year old twerker adorned with a heavy gold chain would hardly elicit a double-take. But while bling and skin have become no more than background noise in cheap entertainment, the same set of ingredients would easily provoke contempt if they were being employed by an alleged creative artist attempting to pass them off as art.

The high-brow realm of fine arts has an avowed allergy to sensationalism. And this is as it should be. In fact, the more polished and aesthetic the delivery of sexually charged images, the more suspicious critics are about the integrity of the work. Is the artist simply trying to seduce the audience with enticing images? Not on my watch, thinks the reviewer with enough righteous indignation to have satisfied Torquemada.

Now imagine that the artist is a relative unknown – a newcomer whose work revolves almost exclusively around young beautiful naked women. In addition, imagine that the artist is a heterosexual male – one that has never graduated from a fine art academy but one who, shamelessly enough, is touting a supposedly feminist agenda. And, as a final affront: imagine that the artist enlists the aforementioned girls to emote, dance, pose or otherwise express themselves prior to having their pictures taken in the raw – and all of this, if rumor has it correctly, without having to pay a pittance for their complicity. Precisely: Player, huckster, user, abuser, charlatan, slick fuck, “Art – yeah right.”

Thus begins our Myth of Kivinen

THE MYTH OF KIVINEN

Like Sisyphus, the hero in our allegoric tragi-comedy spends his days rolling a boulder up a hill only to reach the summit and watch it roll down again – at which point, the futile ascent begins anew. Okay, so it’s not a boulder, but – as is the ultimate nightmare for most artist’s – a Macbook. And it is not a hill he is ascending but an eye-sore of a journey through layer upon layer of photoshop wherein it is his task to render what were once merely powerful pictures of astonishingly beautiful women into more seemingly esoteric and meaningful works of art. As for the precipice, it comes in the form of the Finnish art reviewer – a person who has devoted a lifetime knowing the difference between pornography and art (often having paid a high price for both).

Still, back to our story: Unlike our Greek counterpart, Kivinen lives in a frozen land of swamps (if literal translations are of any comfort) where the hills are flat and the valleys similarly non-existent though endless in their oppressive atmosphere; and, as poetic justice would have it, the hero’s name is a testament to his plight - Kivinen literally meaning 'rocky'.

Sharing much in common with Albert Camus’s existentialist variation on the Sisyphus myth, Kivinen is genuinely happy, hopeful and – as he claims himself – often in a gloriously self-deluded state wherein he convinces himself that international acknowledgement lay just beyond the hill. Although his recent successes abroad make this a viable outcome, what he often finds on the other side of the hill are two Finnish reviewers in the midst of the following conversation:

“I’m telling you, he’s using real models… you know ‘model models’ as artist models”

“Get out”

“And he gets them to undress and ‘express themselves’”.

“Some racket.”

“And then he paints them”

“So?”

“I don’t mean he paints them. I mean he paints them.”

“On them…?”

“As I stand. Or should I say, as his stands”

“Fuck me”

“I assume that’s part of the package”

“Just how friggin’ naïve are these girls?”

“They claim, it’s cathartic. Or, at least, he claims ‘they claim’”.

“Cathartic…? With or without catheter…?”

“Jealous?”

“We should warn people, warn the women… Also, maybe we should learn to paint”.

“Why learn? He never did”.

“You’re shitting me. What’s the guy´s name?”

“Vesa something, I think. Kivinen? Yeah, that must be it: Vesa Kivinen”

Vesa Kivinen - An artist who, admittedly, does love beautiful women, does like seeing them naked, does enjoy sex, and does not have the slightest problem fulfilling these desires without ever having to lift a brush or complete a single work.

As a graduated film director (from UK's prestigious NorthUmbria University) possessing a good sense of humor, with hobbies that include martial arts and music, Kivinen doesn’t need an ‘art project’ to hone in on attractive women. So, the question to the cynics who claim his art is no more than a sleazy rouse, why would someone go through such an elaborate process only to achieve that which demands little if no work at all?

SEX AS A MEANS OF SEDUCTION

As most are aware, there is a complex relationship between seduction and sex. It is no longer just seduction that is a means of attaining sex, but sex that is a means of seducing us into buying a host of things from products to ideologies. Even those that fetishize abstinence rely on sexuality, albeit it in a convoluted way. Kivinen is aware of this overriding theme in our civilization. And whether it is his personal interest in women or an interest based on how our culture views women, the results are the same: Kivinen, the artist, is driven to reflect on the female form and its role in our society. His explorations use an approach that is historical, anthropological, conceptual and highly personal at the same time - the interaction between the photographer and his subject often taking on the form of a psychological exploration, one wherein the model reenacts earlier traumas and gives vent to pent-up emotions and subconscious thoughts.

“Removing someone’s clothing is a pretty quick way to make a person drop their guard on a psychological and interpersonal level”, explains Vesa. “I use hypnotherapy in my work (based on NLP methods) and I start taking pictures once I feel the therapeutic process is under way”. Emotions that are usually reserved only for loved ones are openly explored and those undergoing the procedure often leave having established a better self-image.

PRETTY TOUGH

Besides being young and pretty, many of Kivinen’s models harbor a hard luck story – one that involves a tough past fraught with despair. No matter how hopeful or optimistic the overall themes being explored, there is the recurring motif of an ‘abused person overcoming a trauma and coming into her own’. Why? The answer is likely to be similar to the one I am unable (sic) to answer when asked, ‘what’s this thing you have for crazy girls?’ since what they should really be asking me is ‘how come you’re a bit crazy?’ Though opposites may attract, similarities ‘distract’ in just the right way. They make us confront our own demons by seeing them play out on others. Likewise, helping others becomes a good way to help ourselves. So what’s with Kivinen’s choice of models?

Although Vesa comes from a relatively educated family, the divorce of his parents at an early age sent him spiraling into more than a decade’s worth of abuse. Besides the usual alienation suffered by kids watching the budding passions between new sets of spouses, the young Vesa had the added bonus of inheriting a stepmother on loan from a Brothers Grimm fairy tale.

Although for Vesa quality time with stepmom often included being teased or assaulted, he found that she also delighted in simpler pleasures like watching her two older children taking turns at tormenting him. Ordinary summer outings soon took on the feel of An American Crime - albeit, a slightly milder Finnish version. It was for this reason that one fine day, just moments after arriving to the family lake house, a six year old Vesa tried to drown himself. Though luckily Vesa’s dad was alert enough to thwart the suicide, it didn’t take long before the family was back to business as usual.

When the fleeting joys of summer came to an end, Vesa managed to find the same level of tolerance and physical attention he received at home from among his classmates - many of whom were from very dysfunctional families themselves. On the odd days when Vesa was not targeted by some of the more malevolent delinquents, he would seek out the approval of school bullies who were only too happy to oblige what turned out to be an ongoing campaign for self-disfigurement. It was not till several years had passed - and Vesa realized that love comes in forms other than regular beatings - that he took up kick boxing and things finally began to take a better turn.

If Vesa the artist is drawn to tormented souls with a troubled past clearly it has something to do with his own background. The urge to break through a façade, have someone open up and become vulnerable was born of a need to both help others and himself - a way to get people to reconstruct their personas and become stronger internally. It was this tearing down of barriers and finding the essentially universal symbol lurking within that was present in all his work. Needless to say, it is a process that leaves a mark on both the model and the artist.

Of course, the artistic process is more than just a visualized psychoanalytic deconstruction. Beginning with a dichotomy born of Western Civilization's version of a woman's idealized state and that of earlier belief systems, Kivinen sets the stage for an elaborate choreography – one in which disparate representations of ‘the eternal female’ battle one another on the proscenium of a single human form. In this world, contemporary and ancient symbols are reinterpreted. The body undergoes a metamorphosis. In the end we are watching a parallel plotline where a model’s internalized spiritual adventure alters her external world, while her new external surroundings catalyze changes within.

UNSCRIPTED FILMS

In a sense, the works are stories – simultaneous transformations of character unfolding in a series of stagnant frames. They are films where the dialogue exists in movements, where conversations between the representations we superimpose on individuals and their true selves take place. While the screenplay and directing in these works is an improvised collaboration between Kivinen and the respective model, the final edit and context belong to Kivinen alone.

As a UK graduate, Kivinen initially returned to Finland with the intention of pursuing a career as a film director. Having recently canned a fiction film, as well as having completed several promotional videos and a short, he felt the time was ripe to embark upon a career at home. After approaching a few local production houses, he landed a job with one that specialized in TV-related projects and was soon attached to a weekly show.

Although television gave Kivinen a temporary means of support, it did not take long for him to feel stymied. He was neither part of the inner circle nor was his work bringing him any closer to accessing feature film funding. Not only was he missing the necessary network of friends, but his recent repertoire of works would elicit little clout in any future film-related projects. Kivinen soon realized it was utterly impossible to prove one's worth as a director without having some say as to the content, the crew and the approach. He was drifting further and further from his field of choice. Something drastic had to be done - something that would allow him to continue telling stories while continuing to express the things he needed, something that would not incur heavy debts or rely on the talent of others.

And so, after much deliberation, Kivinen devised an art form that - if worked properly - would be a fusion of several art forms with which he was already familiar - one that would allow him to continue growing as an artist rather than settling into a mechanistic role devoid of creativity. Although Kivinen would still continue to make very powerful smaller films and music videos (a fact I can attest to - having recently co-written an upcoming Paleface music video with him), the majority of his time and talent would now be devoted to an art of his own invention, an art that would allow him to evolve as it evolved with him, and art form entitled, appropriately enough, Artevo.

ARTEVO

While the women Kivinen meets have very different backgrounds, they share one thing in common: a strong physical presence. Working in fields as varied as dance, athletics, modeling or drama, they are in command of their bodies and able to express a wide range of emotions through gestures. Stripping them naked and slowly covering them in body paint, he provokes them to explore a hidden range of emotions while capturing each moment and chronicling their development. It is a rite of passage wherein the models themselves have become voyeurs of their own unmaking and reconstruction. Viewers can sense how each model invariably undergoes a series of motions that slowly drift from rigid, preconceived and self-consciously aesthetic movements to more archaic and ritualized patterns.

Exploring subjects like abandonment, loss, shame, love, and guilt, Kivinen allows for vulnerability to be reborn. With the paint as their shield, the girls are transformed into an anthology of fragmented nerves, sinews, moments, moods, and spiritual events - a human Petri dish from which to grow anew. As body parts become indistinguishable from emotional formations, the entity that grows is one where the signifier and signified are equal in importance. Although the women are photographed naked, there is a noticeable absence of erotica, whether explicit or otherwise.

Kivinen's final stage of the process means integrating the images of the model with a harvested background - one that is itself a composite of many earlier painted objects, earlier photographed works, and superimposed layers of colors and tones. Eventually, a new primary subject emerges from the ongoing dialogue. Rising from the chaos of competing images, a newly evolved center piece is born.

Rather than subscribing to the age old ‘kill your darlings’ adage, Kivinen allows himself to be 'seduced' a final time. His initial concept is seduced by one of many seemingly inconsequential darlings. It is this new idiosyncratic darling that calls the shots. It determines all that follows. In Kivinen’s parallel universe, rust from an abandoned crucifix can give birth to a planet where a woman’s face blossoms from the dried stem of a plucked flower.

With the meanings behind each symbol remaining in a permanent state of flux, the one solid point of reference becomes the timeless shapes. In the end, contemporary society can be seen as an ancient artifact – our advanced terminology having become no more than primitive etchings on the wall of an undiscovered cave - while our more ancient myths revive in a contemporary setting.The harmony that emerges is one that fuses dissonant worlds.

QUOD LICET LOVI, NON LICET BOVI

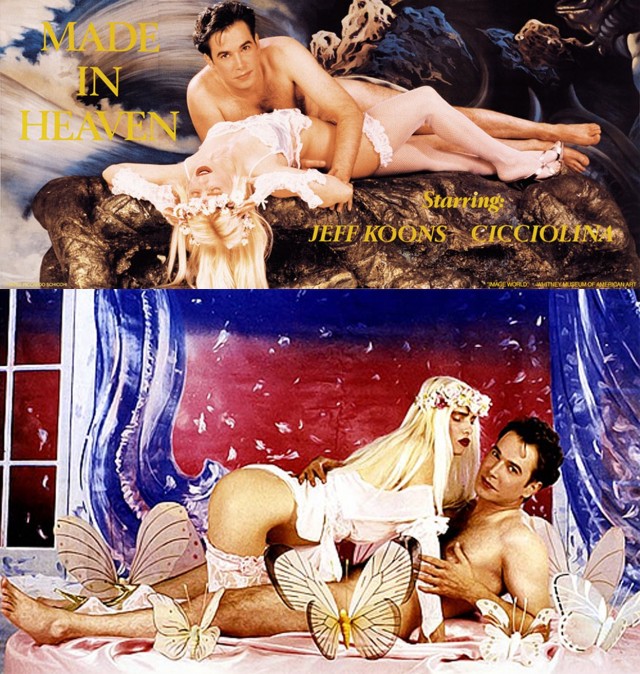

Back in 1989, Jeff Koons employed Hungarian porn actress (later to become Italian parliamentarian) Ilona Staller aka Cicciolina as a model in a photo, painting and sculptor series for the Whitney Museum. Though the overtly sexual poses caused some controversy, the works were eventually celebrated. Koons was a star – a beloved international one, one that was treated as a demi-god when he came to Finland years later. I know this for a fact since I was asked by the local curators to interview him and review his work while he was on a visit here. Shortly after my piece was published in a magazine I regularly contributed to in New York, I began to receive invitation upon invitation to local openings – so many in fact, that I ended up pretending to have returned to New York a month and a half earlier than I had.

The reason I bring this up is because not a single local curator or journalist I had spoken to at the time felt that Koons was exploitative in any sense at any time during his career. Although, I did bring up the Staller works, most agreed they were interesting social commentaries on media and sexual exploitation within media rather than being pornographic in nature themselves. Some even joked about some American art reviewers being puritanical for having ever questioned his work.

Ironically, many of these same reviewers greeted Kivinen’s collaboration with ex-Miss Finland, Noora Hautakangas, with abject silence. The fact that Kivinen's works were not only far less sexual in nature than Koons’s work did not seem to matter.

Kivinen had met Noora while on a photo gig for the Miss Finland 2010 contest at the Grand Casino Hotel –an event that left him feeling markedly queezzy due to the ‘meat market’ mentality of the proceedings. Responding enthusiastically to samples of Kivinen's works, Noora was pleased with the notion of collaborating on a project - one where both agreed to donate 50% of the generated sales to the care of the elderly, a subject that troubled many at the time.

The project itself relied on another female counterpart – Mia, a girl who referred to herself as the ‘dead girl’, after spending a year in a near stupor in a psychiatric hospital where they diagnosed her as a schizophrenic. The message was far from banal. For Kivinen, Mia represented a sensitive being who in a tribal environment might have been celebrated as a shaman; while Noora represented the ghost in our contemporary machine – one which had been turned into a commercial commodity despite the powerful personality that lay beneath. In a sense, both women were suffering from harmful contemporary labels. Alluding to concepts as interesting as environment altering our genes, and expectations embalming our personalities (turning many into zombies of convention), the works were devoid of sensationalism.

Turning Mia into the Finnish Maiden (someone who would likely have been celebrated by our pagan ancestors) and Noora into a spirit (one whom society stifles beneath superimposed commercial and nationalistic values), Kivinen’s images were anything but pornographic. Nevertheless, the local response seemed to be: Cicciolina is art while Kivinen is ‘porn with a few brush strokes for good measure’.

PART 2 A COMIC TRAGEDY OF ERRORS

LOST IN UNTRANSLATED FORM

When Michael Schwartz - a Columbia University graduate who is a Professor of History and Philosophy of Art - recently saw Kivinen’s work, he wrote, “Vesa’s art is amongst the most integrally advanced in the history of Western abstraction – no small claim, but one backed up by the works themselves. Rather than abstraction as a fleeing from life, his works are a diving into the incarnate mystery of human being — direct celebrations of the fullness of Life.”

Although Mr. Schwartz is a well respected authority on art, his appreciation did not translate into local attention let alone – that most unattainable of states - recognition. The doyens of the Finnish art world would not be swayed by some aficionado with an international reputation. Everyone had their off days. Perhaps Schwartz was getting old and hankered to see photos of naked women marred in paint; or worse, perhaps he had confused Kivinen with Kivits, the sweetheart of the ‘flower and vase school of painting’. Schwartz’s comments, they concluded, should be taken with a grain of salt and a small handful of LSD. After all, one kind American does not a reputation make. They would rely instead on their better judgment – meaning, Wikipedia and the Helsinki Sanomat.

Writing his name into google, K-I-V-I-N-E-N, the experts felt immediate vindication. Kivinen was a relative unknown. So why would they blemish a near perfect record of anonymity with signs of life. In addition, Kivinen’s Wikipedia page had a glaring omission: there was no mention of the artist ever having attended Helsinki’s University of Fine Arts. The whole thing reeked of autodidact. The best thing to do in a situation like this was keep a safe distance from emails and phones, and wait for the entire Schwartz incident to pass.

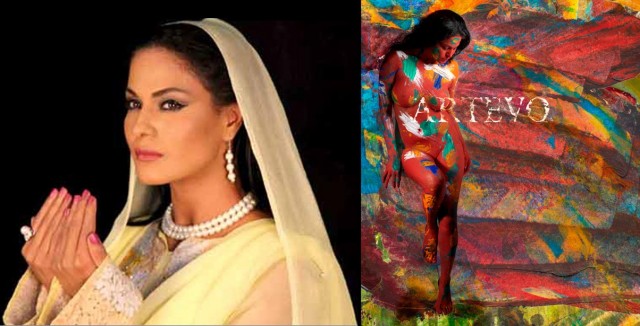

If an image is worth a thousand words, they reckoned, it could very well be that Kivinen’s images were fluent in a language with which none of them were familiar. Besides which, the only mention they could find of Kivinen in the Helsinki Sanomat – the worthiest daily given it was the only one available – was a dismissive footnote appearing under the picture of a renowned Bollywood actress where Kivinen is quoted saying: “if they tell you not to dance, you should go ahead and dance anyway.” Although several curators racked their brains trying to recall if they had ever seen Kivinen swaying in a saree or taking part in the local tango competitions nothing came to mind. What was that whole dancing mess about anyway if not some desperate attempt by Kivinen at getting some ballerinas attention?

BOLLYWOOD'S TICKING BOMBSHELL

At this point, it’s necessary to digress a bit, if only to explain the elusive photo of Kivinen standing back to back with Bollywood star, Veena Malik. Born into a Muslim family in Pakistan, Malik had been abandoned by her parents at an early age and brought up by her grandmother. Working her way through school by modeling, Veena eventually graduated University with a BA in sociology and psychology while making a name for herself as an actress in Lahore’s film industry (Lollywood). Making a successful transition to Bollywood, the seductive young actress eventually achieved celebrity status. Because of the exposure and her very humble beginnings, she soon landed in some controversies among them the very recent one that seemed to be getting the most attention: a Muslim cleric had accused her of dressing provocatively and being a bad Muslim. Instead of ignoring the charge or defending herself as many in her situation would have done, she dauntlessly returned the attacked, calling the Mufti a fraud while accusing him of breaking his own laws by staring at her for longer than two seconds – which according to scripture is against religious law if she were indeed the lewd woman he had claimed she was. She went on to say that unlike many of the clerics who had sexually abused children, nothing she was doing was undermining morality.

Though many feared for her life, Veena went on acting, committed to the idea that her point of view should be heard at any cost. Despite an attempt at her life - an incident where two tanker trucks nearly crushed the car she was driving - Veena managed to survive unscathed. With several well-paid bodyguards on her payroll and the admiration of the Indian public, Veena went on with her career.

Inspired by Veena’s fiery personality and, as Kivinen opines, “her grace under pressure”, Kivinen thought Veena would make a most inspiring model. After a series of circuitous correspondences, he managed to get an email directly to her and, much to his and everyone’s surprise, she said ‘yes’ and agreed to meet Kivinen in London with the intention of eventually flying to Finland to have herself body-painted and photographed.

During the ensuing months – both while preparing for Veena’s arrival in Finland and the long interim prior to completing the works - a lot would happen in Kivinen’s life. The works and the stress surrounding what could be a religiously touchy issue would exact a heavy toll on his health; this, while the lack of local attention in the later months would leave its scars on his emotional well being.

In an effort to protect Veena from the possible onslaught of religious fanatics, Kivinen decided to pay an extraordinary amount of attention in ensuring that the project could not be misunderstood. It would be morally irreproachable and avoid sexually suggestive imagery. Eschewing the politicizing of religion, he immersed himself in a comprehensive study of women and their role in religion. For Kivinen this necessitated a full commitment in researching world religions and their respective traditions. Since artworks relied on visuals, the study would also entail a comparative understanding of the symbolism used in different traditions and the female’s place within the respective iconography.

Aware that Veena Malik oozed sexuality in her Bollywood roles, Kivinen wanted to avoid all allusions to seduction. There would be no erotic devices in the works. Although this would be the first time that Veena Malik would be filmed naked, these images would, paradoxically, be the least sexually loaded of her career.

Given that Finland regularly awards a disproportionate amount of attention to art that bathes itself in the holy unction of a cause, it seemed inconceivable to Kivien that his work with Malik would be overlooked. And yet, the local publications were going beyond inconceivable, and would stop at nothing short of incomprehensible.

There was persistence to local indifference – a continuity that not even divine intervention could fluster. In a country that celebrated a host of mediocrities who paraded quasi-subversive messages with the depth of a junior high school protest sign, there was not a word being spared on Kivinen and Malik’s collaboration.

As magazines clamored about outdated risqué works whose sociopolitical commentary can best be summed up as ‘down with McDonalds and up with equal rights’, Kivinen’s voyage through belief systems that ended up oppressing women - after, paradoxically, casting the female form into an idealized symbolic role - was all but entirely ignored. Here was the internationally controversial actress Veena Malik - a woman who had received death threats simply for immoderate dressing – posing entirely nude, having her body painted only to be deployed within a work of art and the best that local publications could muster was a cultural version of: what’s a nice girl like you doing in an art work like this?

Working around the clock to perfect each image, Kivinen had little time to eke out even a meager existence. If the phrase ‘starving artist’ had ever held some romantic overtones, the last few months of herbal teas, dried fruits and a surfeit of pain killers prescribed for his bad back were enough to rob the words of their luster. After a particularly bad bout of pneumonia which – according to the doctors who were treating him the emergency room – could easily have robbed him of his life, Kivinen was convinced he had to start taking better care of himself. Being released just in time to finish up the last works, Kivinen was set for the London opening.

On the day of the opening, a prominent group of Pakistani and Indian journalists gathered in the gallery; a dead silence pervading the room. It was as if the slightest mistake could have set off a Fatwah. All were aware what it meant in a Muslim community for a woman to pose naked. But no sooner had the people seen the works than it became evident that what they were witnessing was art. Not even the most hardened skeptics were able to fault the works for being arousing or pornographic in nature. Though Kivinen was still worried about the consequences of offending the Muslim community, he realized that even laymen instinctively knew that these works were spiritual in nature and not even remotely exploitative.

THE MESSAGE IS NO MASSAGE

Kivinen explained his conceptual frame of reference. While Islam and Judaism forbade the depiction of God – the logic being that God is an abstract whose form man can’t possibly hope to grasp – Christianity’s approach meant seeing the divine presence in the most ordinary of human images. He was excited to notice that the concepts did not contradict one another and were instead different approaches to the same premise. The more Kivinen studied the differences between each religion, the more he saw similarities in terms of their aspirations.

In Flower of Life we see 6 images of Veena – the geometric shape alluding to the Merkaba (commonly noted in the Star of David), the very shape that makes up the chariot which is capable of ferrying us to the afterlife. In addition, there is the reference to angels as evoked by Judaic, Christian and Muslim traditions. Looking at the six Veenas one also gets the sense of an episodic circular drama unfolding – a series much in keeping with the Hindu idea of existence; while from the outside, all six look as if they are part of a chaotic development – chaos itself being an association to the Chinese traditions. Although Judeo-Christian and Muslim beliefs see life as an interim prior to a heavenly (or hellish) afterlife, many pagan traditions see life as the most heavenly part of the cycle while afterlife represented a threatening realm akin to hell. In Kivinen’s world, these complex belief systems are aligned and differences depend solely on the viewer’s perspective.

As a perfect example of how each model’s personal journey resonates within a larger eternal theme, one need look no further than the work entitled Mohenjo Daro, named as it were after a Pakistani excavation site where an ancient Bronze figure depicting a precocious girl dancing had been discovered. In this frosty realm of water and ice, parallels to Malik’s own life are played out. She is, after all, the precocious dancing girl who dances on despite the authorities who try to extinguish her fire and despite her own internal pains and fears.

Little could Kivinen have guessed that by making a simple reference to Malik as the girl who “dances on despite being told not to”, the comment would become the criteria by which his work would be misunderstood by the Finnish media.

While the BBC reported on Malik’s irrepressible spirit and her participation in an art show, and while Paksitani reporter Alsha Farooq referred to the project in terms of it being “a reinvention of cultural norms as we understand them”, and while over 300 million people throughout India, Pakistan and the far east had reportedly became exposed to the event, the reviewer from the Sanomat wrote off the entire work as an odd little event where a breast-obsessed local photographer who wants everyone to dance took some pictures of a well known Bollywood starlet.

Being lucky enough to have had Malik briefly act in a comedy sketch I had written, I was well aware that Malik was anything but frivolous. She was interested not only in how funny a given sketch was but what meanings existed in the subtext. Upon being translated the Sanomat’s review of Kivinen’s work, I could hardly believe that the critic in question had seen the works he was purportedly writing about. From the sound of the report, the entire farrago was no more than a marketing gimmick between a desperate porn-addicted local and a silly Bollywood starlet who should have known better.

Scanning the article, I immediately jumped on Kivinen’s website. Had Kivinen really altered his style so much? Had he really succumbed to taking Penthouse magazine snapshots – snapshots that were filled with crucifixes and the occasional bronze elephant statue? As I saw what amounted to heavily textured abstract works where the images looked less like photographs than Degas oils, I was confused. Perhaps Kivinen’s recent phone call to me was on the money after all. Perhaps the local media was really dead set on seeing him in a certain light and it made absolutely no difference what he was presenting. With subject matter devoted to how religious traditions perceive women, it was clear that Kivinen was not just taking a series of pleasant nude pics. What I initially assumed was paranoia on Kivinen’s part sadly turned out to be a valid gripe.

Watching the works in question, one is provoked to think. Although Kivinen never mentions this, shortly upon seeing the works I had the immediate sense that when it came to women being depicted by religion, every pedestal was a gallows in disguise. The worship of female purity had cast them into the role of the martyr. The spirituality evinced by a nude woman was sacred in comparison to the pornography that religion had become – clerical misinterpretation coupled with political machinations had undone the very thing which had inspired many of the religious beliefs in the first place. Okay, so maybe this was just my personal take on the paintings and not the intention of the artist; but one thing was certain, it did prompt the viewer to think. How could the Finnish reviewers have missed this aspect of the work? And more to the point, how could they have seen an exploitative element in any of it?

Although Kivinen never overtly turned the art works into a message attacking the misappropriation of religion by fanatics, his works – in my opinion – were far more loaded and ‘activist’ in their nature than the heavy handed proselytizing that many of the artists who jumped on the bandwagon of ‘trendy subject matter to be pissed off about’ were involved in. If the reviewers were not all out to get Kivinen – a notion which bordered on paranoid delusions of grandeur – than what was the cause of such a muted response?

And it was then it dawned on me. Local reviewers weren’t actively trying to sabotage Kivinen’s effort in the least. They were simply afraid of being the first to take any kind of position on a work that had not already been appraised. Kivinen’s work had no points of reference. Unlike most local artists, Kivinen wasn’t recycling successful foreign approaches and adapting them within a local context. He wasn’t replicating a preexisting genre or playing out well known devices. Whether for better or for worse, Kivinen was - as childish as this may sound - an original. If anything, he was an artist in the most ambitious sense of the word and had tackled concepts that were well beyond his expertise or even skill set - a mistake often attributed to historical figures in art. No matter how hard I looked, I found no real critiques… no one who loved the work for possessing certain qualities, and no one who hated it for having certain flaws.

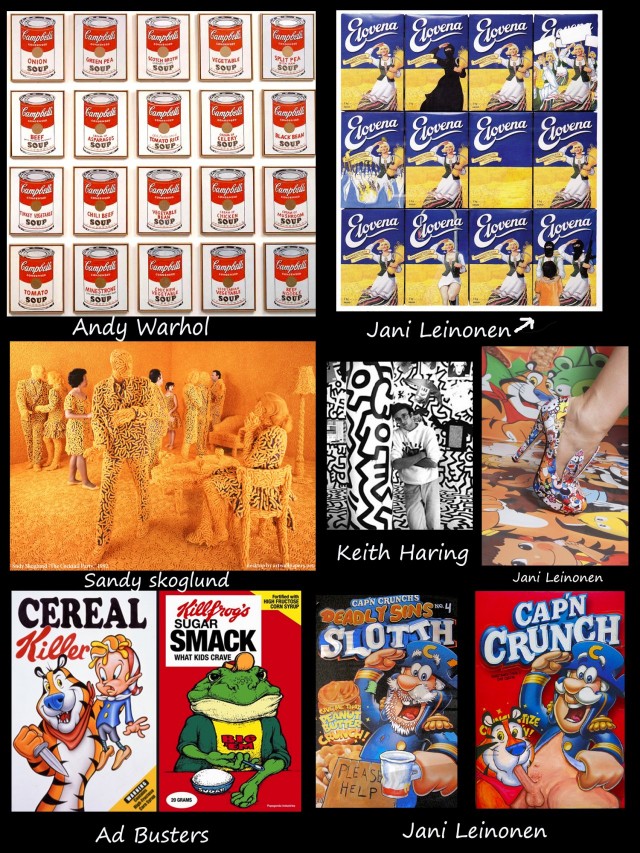

Jani Leinonen could be assessed; it depended on a tradition that ran from Warhol’s obsession with consumer products to Damien Hirst’s respective installations such as Pharmacy and Trinity, to the twenty five year history of Ad Busters doing parodies on commercials. The territory had been marked out in advance even if the execution had not. The same went for local photo artists who were influenced by Cindy Sherman as well as a series of slightly older painters who were caught somewhere between Lucien Freud and Georgia O’Keefe. As for the ascetic world of newer Finnish artists like Grönlund and Nissunen, it was comprehensible to reviewers when understood from the perspective of local aesthetics in design and architecture.

There is no intention to downplay the significance of the aforementioned works since similar comparisons could easily have been made about masterpieces by impressionists – especially when examining works of Monet and Morisot or Degas’s Absinthe and Manet’s the Plum. But, needless to say, when it came to Salvador Dali one would have had to depart from the world of Fine Arts and examine the poetry of Paul Èluard or the films of Luis Buñuel to find parallels. Likewise, in Kivinen’s case one would have to draw parallels to works outside the frame of contemporary directions in local art. Would doing so automatically make Kivinen’s work more significant? No. The criteria would still depend on the level of execution as well as the overall impact. But the problem wasn’t that reviewers were criticizing Kivinen’s works but that they were avoiding the subject entirely as though they wouldn't know where to begin.

Whether right or wrong, reviewers exist solely in order to put themselves on the line and proffer an opinion. There was no harm done when some esteemed reviewers a century ago wrote that ‘Dali is at best a graphic artist with clever surrealistic ideas but has no strong gestures or tactile sensibility’ while others celebrated him for his wild imagination and psychological insights. Their job isn’t to be right or wrong but to make us aware of the criteria involved when judging a work. ‘Kivinen’s work is an engaging use of several different mediums’ or ‘Kivinen’s work is a muddled philosophical treatise sporadically infusing spirituality, anthropology and symbolism in a contrived harmony that smacks of New Age’ – they are free to make either claim. What they shouldn’t do is to sit back in the hopes that a reviewer from abroad will put it into context for them in a decade or so.

Sadly, it is my experience that the majority of Finnish reviewers are never wrong. And this is far worse a problem than never being right since it means they spend their lives restating parallels that others have drawn for them rather than coming to conclusions on their own.

A NIGHT AT THE OPERA

Imagining Kivinen’s relationship with local culture in fast forward conjures images of a Marx Brothers movie: anarchy meets high flying zany antics while egos soar between heavenly aspirations and abject poverty. A memorable chapter in Kivinen’s bildungroman of misfortunes is his escapade into the fanciful world of classical music. In the Marx Brothers film, A Night at the Opera there’s a memorable scene where Chico – being suspicious of Groucho’s explanation about a line in a contract – responds: “hahaha – you can’t fool me. There ain’t no Sanity Clause!” Kivinen should have considered this line and his own mental state before making a contractual agreement with opera diva Elizabeth Wärnfeld and the renowned Santa Claus of Classical music, the much lauded conductor, Leif Segerstam.

The heat was on. Segerstam was in one of his inspired moods. The composer of hundreds of ‘free pulsation’ symphonies - where musicians follow notes but often start and stop at their own discretion - was in the passionate throes of working on yet another in a series of amorphous symphonies. This one was for Elizabeth Wärnfeldt – an opera singer of Wagnerian proportions with a rumble of a laugh that set Segerstam’s own hefty mass quivering with delight. Between copious amounts of wine and food, the two enraptured souls were discussing the ‘nowness’ of music, the mothership of composition, the satellite of conducting, the orbiting listeners and the need to order another drink before going to the toilet. ‘High culture’, thought Kivinen, doing his best to become an affable third wheel in their seemingly cryptic conversation. After hearing the pair mention something of a spiritual nature, Kivinen took the opportunity to draw parallels between their observations and the subject matter in his own work -samples of which he happened to have with him on his trusty ipad.

Flip-flip- yes, the women in the paintings were real; flip, ´yes, he could create a similar one as a backdrop for a set’; flip, flip – ‘of course it could be projected and work on stage’; flip ‘why wouldn’t he use Elizabeth herself for the piece’; flip, ‘it’s a deal’. It was perfect. No more would people be commenting on the fact that he only made works with young attractive models, he would now create a masterpiece with the Swedish Brynhildr. Although he would need more paint than usual, this was precisely the sort of event that would finally get him the kind of recognition he so justly deserved. Here were two massive figures in the world of culture and both of them had weighed in on his art. Gravitas, at last.

‘It was an honor to work with a legend’, ‘Opera - his mom will be proud’… Although, Kivinen repeated this like a mantra, it became increasingly difficult to overlook the fact that he was losing weight in nearly direct proportion to the amount the two lovebirds - Wärnfeldt and Segerstam - were gaining. Having spent the better part of two months working on the show’s center piece - a massive portrait of Wärnfeldt as an Icelandic Marianne, Goddess of Liberty (or was it Libertine, he could no longer recall which) – he had had no time to support himself. Besides the hours spent assuring Wärnefeldt that the portrait made her look like a perfectly svelt Valkyrie, he had also - catastrophically enough - agreed to taking free PR pictures to promote the event. The result being, he had given up all his potential money gigs for an education in opera - one which by-passed Puccini and Verdi and focused almost entirely on the oddly disquieting phrases by Olson, Olsson, and Olofsson - three Nordic composers who sounded more memorable as a law firm than as individual composers.

His desktop had, in like, been occupied by Wärnfeldt: Wärnfeldt in the meadows, Wärnferldt giggling amongst the pine cones, Wärnfeldt preening in a snowy landscape. Should he have lost his laptop, anyone seeing the images would immediately have assumed it belonged to someone with a school boy’s crush on the grande dame. It didn’t help that Wärnfeldt incessantly teased Segerstam with SMS’s like ‘must cancel, darling –our young artist insisted on some lakeside pictures’.

Though the work involved felt as endless as Der Ring des Nibelungen, Kivinen knew that what awaited him was Valhalla: a symphony with his massive portrait projected on stage, a more complex series of his works to accompany the eventual opera, a film based on similar aesthetics, a long and promising tour that would take the three of them to all the opera houses of the world, and even a published book of Wärnfeldt’s poetry with Kivinen’s art that would be circulated globally. Although the only remuneration Kivinen had received so far was a camera that was good enough to give him the resolution necessary for the work in question, he was confident that all his diligence would eventually pay off.

Although Kivinen had long suspected that life had degenerated into a more macabre version of La Bohème, it was not until opening night that he realized he was Mimi. He was told in no uncertain terms: no matter how many books with his images were sold, he would not be seeing a dime. All proceeds would go to Warnfeldt and her restaurants of choice.

Finally, intermission. The two divas sat in the lobby like Foghorn Leghorn and Obelix signing away copies. A gaunt Kivinen passed over them like the memory of famine. 'Ungrateful ghost, sulking in the periphery'. How dare Kivinen not join their autograph posse and sign each copy. The two were visibly agitated by Vesa's lack of interest. As for Kivinen, he hung with his grandma.

Soon, Segerstam's own composition was underway – an erratic flurry of dissonant chords that started, jolted and stalled from open to finish. It reminded Kivinen of his career. Splattering to an ignominious close, the last notes sounded, making Kivinen think how unlucky it was that his grandmother though quite old was not hard of hearing. The symphony ended to warm applause. These clapping hands were the nicest sounds to have been made over the last half hour and the audience knew it. They continued at it as though afraid a possible encore might begin should they stop.Segerstam and Wärnfeld receiving bouquets while some unknown figure discretely passed a third group of flowers over to where Kivinen was sitting. It was all handled inconspicuously enough. Aside from one highly suspicious florist, few noticed his presence. The two looming figures on stage eagerly continued to bow.

A day after the opera was over Kivinen received his thank you note in the form of an official email telling him he has no right to put any of his own images online. As opera’s go, this one had ended like Don Giovanni with a feminine image as large as the statue of the Commendatore escorting our artist to a hell of his own making.

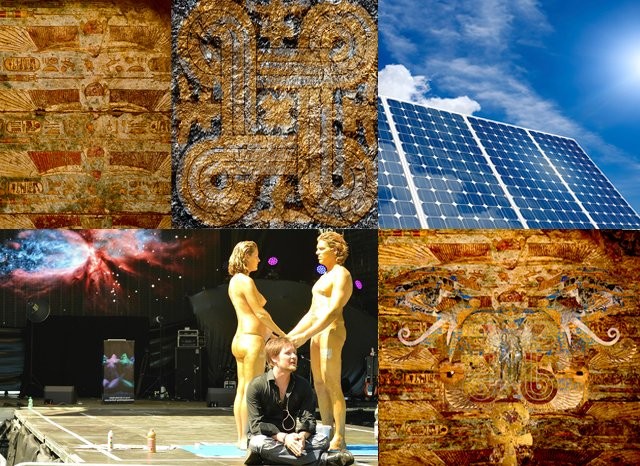

PART 3: THE LAST LAUGH

Most recently, Kivinen was asked to participate in the 2014 World Body Festival in Austria. With 30,000 visitors, 400 photographers, and the most prestigious names in body painting, the venue allowed Vesa an opportunity to create an installation of his work on the main stage in front of a live audience. Painting life-cycle related symbols from the Kalevala and several religions onto the bodies of a young pregnant couple, Kivinen projected the couple’s images onto a large screen where earlier images from the world’s largest solar panel as well as images from the ceiling of Luxor’s temple of Karnak had been deployed as a background. Realizing that there’s a show business element to all art forms that rely on a performance, Kivinen, of course, made sure to play background music, tell stories and even guide the entire audience through an engaging meditation process. If tears and applause are anything to go by, it was an unmitigated success. Well, everywhere that is but at home.

WHAT PRICE SALVATION AND SALIVATION

Although there are many who have no problem listening to actors or rock stars voicing their opinion on a myriad of subjects they know nothing about, the very same uncritical thinkers don’t waste a moment making disparaging comments should Kivinen mention his method for pricing his own art. Whether his process would actually alter our usual means of pricing is another matter entirely since stayed and tried methods depend on far more than logic or clever reinvention. But there is something enticing in the idea that speculators and risk takers should be automatically rewarded for their efforts while those who buy something after it has become a commodity should pay more.

In fact, that is in theory how it already works since unknown artists who become celebrities often make fortunes for those who invest early. The only nuance in Kivinen’s approach is his application of the aforementioned logic to the world of copies. Since his works don’t rely on a classical lithograph type plate, a larger number of prints do not detract from the quality. Photo prints retain the quality of the original no matter how many times they are printed. So why are people paying more for an original print than a later print? Is there a reason to arbitrarily decide on how many prints will ever be made when a larger number no longer reflects a gradual worsening of the product? Is there a reason for artificially curbing the number so as to make it rare?

Kivinen decided the price should be based –as it was originally intended - on rewarding those who scout out genius and take risks. In practice this means: those who buy the first print pay the original price; should someone want a second print, a second print will be made at double the price of the original; should someone want a third print, it will be double the price of the second… and so on and so forth exponentially. Does this sound crazy? From a relatively unknown artist – any nuance sounds crazy. The idea that he isn’t following a given genre and has ambitions to reinvent the way all of pricing works would either make him an overlooked genius or a nutcase, and calling someone a genius can easily make a critic sound like a nutcase.

If, as they say, opinions are like assholes then Finnish reviewers are guaranteed to remain in a permanent state of constipation. The fear of getting it wrong is endemic to local culture. I recall a very telling experience with a Finnish record label. Several of us who were working with a recording artist – as well as the artist herself - came to the conclusion that her music would benefit a great deal from a major overhaul in genre. The compositions as well as the singer lent themselves to an indie style far more than to the metal production from which she had been suffering for years. When we proposed the change to the A&R – an otherwise very respected musician who fearlessly experimented with his own music - he answered: “You’re right. I totally agree. But you will never do that, at least not on my watch. Because if there’s even 1% chance she’ll fail with anew style – it’ll mean my job. If she fails doing what she’s always done, all they’ll say is *that was to be expected’.”

Despite rumors to the contrary, the problem reviewers have with Kivinen’s art isn’t the nudity. In a Scandinavian country with such a healthy attitude towards nudity, it would be highly unlikely. No, the problem is that reviewers risk being caught in a compromising position. After all, Kivinen’s work not only contains nudes, it contains pretty nudes… pretty nudes in aesthetic settings, no less. It looks almost decorative and when was the last time anything of depth had adjectives like ‘pretty’ or ‘harmonic’ preceding it? And who would take the risk to be the first to say otherwise? No, that settles it. Kivinen’s work can’t possibly be art. Neither is the subject matter repugnant nor is it executed with methodical minimalism. And where is that devil-may-care final flourish that makes it look unplanned? It looks too well thought out and too damn pretty. There is an awful sense that his works are even making an attempt ‘to say something’. Local art abhors saturation as surely as nature abhors a vacuum. In addition, there is a debilitating air of hopefulness - a fatal flaw given the zeitgeist, if ever there was one.

Even worse, Kivinen – like all of us - desperately wants to be liked; and he tries to explain his concepts in a way that most self-taught people do - by citing the many different thinkers they admire. It is for this reason that many overlook the fact that although Kivinen desires to be liked, his art does not. His works are ambitious, complex and, luckily refuse, even his own explanations of them.

As for locals critics who would quip ‘what price salivation(sic)?’ seeing nothing but exploitative nudism in his art, perhaps this would be a good time for a reevaluation – or, more appropriately, any kind of first time evaluation whether favorable or not. After all, it is easy to imagine how difficult it must be for Kivinen to explain potential foreign buyers why his own country of origin has not said anything about his work.

On a recent visit to Finland, the renowned Egyptologist, John Anthony West met up with Leena Ahtola Moorhouse - a local acquaintance of his who happened to be the head curator of the Ateneum Museum. Having been invited to an important museum event and having, coincidentally, been familiar with Kivinen, he simply couldn't resist asking Moorhouse what she thought of his work. Slightly flustered but poised, Moorhouse gave way to a sophisticated titter before leaning in and girlishly confiding: "Oh, Mr. West,really... Kivinen's work...? - it's simply too daring, you know".

Perhaps, Moorhouse is right. At least if the definition of 'daring' betrays its linguistic origins as in 'how dare he'. How dare Kivinen put reputations on the line by showing unsolicited works without art school pedigree and credentials. Then again, all it takes is that one odd article, that one off review, that one "daring" moment when someone abroad unwittingly writes something favorable and creates a buzz. After that, locals will follow in droves. Once free of the burden of having to form their own opinions, Finnish reviewers will sit back, nod knowingly and enjoy the pieces without fear of repercussions. How liberating it will be for them after someone finally steps ups, names the genre, and tells all the uncertain souls 'it’s perfectly okay to like or dislike Kivinen's art - it's perfectly admissible to have one's own opinion, after all.